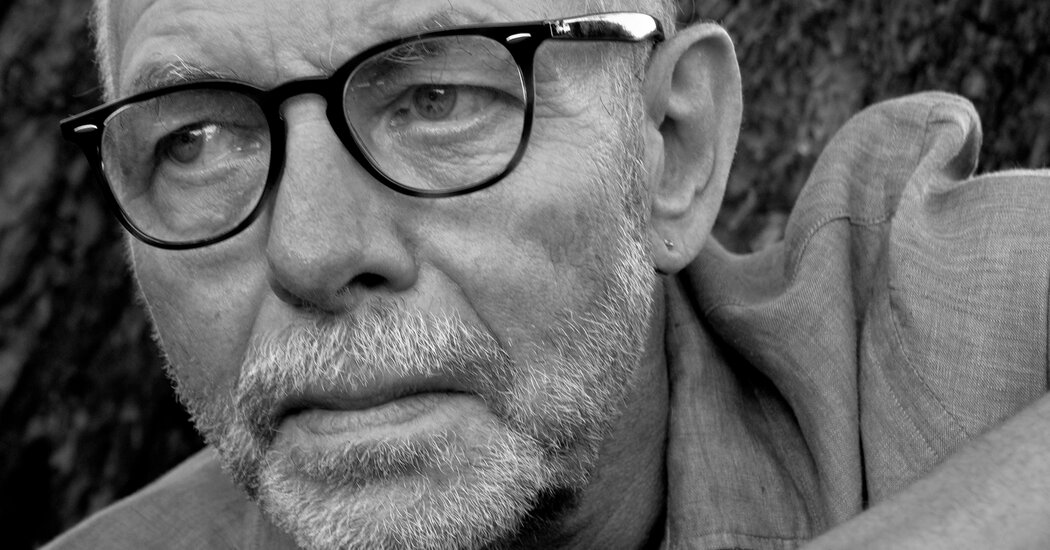

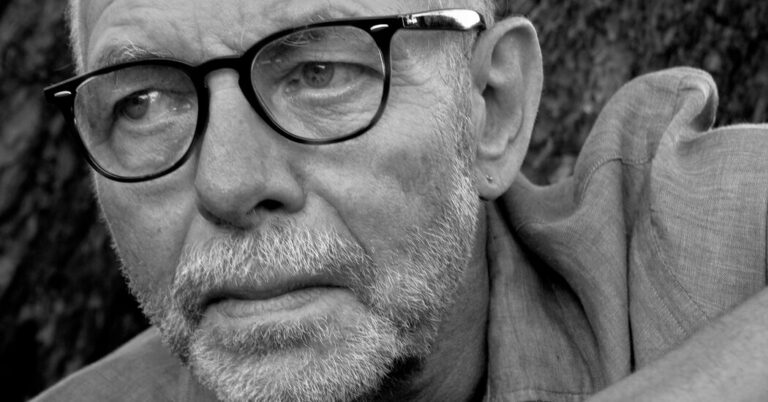

Pierre Joris, poet and translator who faced some of the most difficult verses of the 20th century, making the complex work of the German poet Paul Celan in English, died on February 27 in his home in Brooklyn. He was 78 years old.

His wife, Nicole Peyraffite, said that the cause was cancer complications.

Joris was the author of dozens of volumes of his poetry and prose. But much of the work of his life was spent grappling with Celan’s poetry, which many critics considered, in the words of a scholar, “probably the greatest European poet in the post -war period”.

That greatness comes with a hitch for readers, however: the diabolical difficulty of a writer whose texts were trained and deformed by the chogiol of the Holocaust – “what happened”, as Celan called it. Both his parents were assassinated by the Nazis in what is Romania today. Less than 30 years later, Celan ended his life in France, jumping into the Senna river in 1970 at the age of 49.

In the middle, he felt he had to invent a new version of the German, the cultivated language that had grown as a member of the Jewish bourgeoisie in CzerNowitz (now part of Ukraine). But he had to be purified by Nazi barbarism.

The result would be “truly an invented German”, as Mr. Joris (pronounced Jor-Iss) wrote in the introduction to “Fanti-Turn in Timestead” (2014), his translations of the subsequent works of Celan.

A public reading of the best known work of Celan, the hypnotic “Death Fugue”, was “an epiphany” for Mr. Joris as a 15 -year -old student in his native Luxembourg, he told the New York State Writers Institute in 2014. The poetry was inspired by the murder of Celan’s mother in 1942.

“My hair was in order,” said Mr. Joris.

Poetry, as translated by Mr. Joris, begins:

Black morning milk, we drink you at Dusktime

We drink you at noon and Dawntime we drink at night

we drink and drink

But “Death Fugue” was an initial work, later partly disconnected by Celan. It is the enigmatic poetry of his last years that Mr. Joris was determined to face.

The “non -translatability” of the late Celan “is a Truism in critical discussion”, wrote the poet and critic Adam Kirsch in the revision of New York books in 2016, in a largely favorable review of Joris’ work.

Joris faced the challenge. “He made the impossible, because it is impossible to translate Celan,” said the Ruman-American poet Andrei Codrescu in an interview.

In eight books of translations published for over 50 years, starting from when he was a bard college graduate in 1967, Mr. Joris tried to make the English experiment Celan with the language: to transmit what cannot be made in words-Holocaust and his many consequences, physical and psychological-creating an open poetry of multiple possible meanings.

Celan’s poetry “is the work that came out of the mid -20th century which turns most directly to the disaster, if you want, of western culture”, said Joris to the revision of the books of Los Angeles in 2021.

“Absolute poetry – no, certainly cannot exist,” said Celan in a famous speech in Germany in 1960, when he was awarded a literary prize. And so the translator of Celan has latitude, of which Mr. Joris took advantage – mostly of good effect, in the eyes of the criticism.

“Celan’s vision is destined to destabilize any concept of poetry as a fixed and absolute artifact,” said Joris in his introduction to “Fanti -turn”.

At the level of the words themselves, a translator could therefore opt for what Mr. Joris called “elegant, easily readable and accessible American versions of the German”. He rejected that approach.

Instead, he tried to recreate the many surprising neologisms of Celan in English, as Princeton’s critic Michael Wood noticed, citing, among many other examples, “Started-over”, “Inside”, “Night cradiate”, “removed from a day”, “all over the world” and “more heart”.

“There are some words that I am still looking for, that I have not yet found,” Joris told the writer Paul Auster in a public dialogue at Deutsches Haus in New York in 2020. “Farish polysemy”.

While some critics have found this heavy approach, Mr. Wood praised Mr. Joris’ adventurosity. “A poet himself, he is not afraid of strangeness in the diction,” Wood wrote in the London review of the books in 2021. “He does not seek him, but he knows when he plays well. He brings us closer to Celan at work, shows him that leads the words and be guided by them, while Celan himself describes the process.”

In an interview with the poet Charles Bernstein in 2023, Mr. Joris referred to Celan as “the survivor bruised, tired and suspicious who prefers to communicate through his poems, poems intended to” testify for the witness “.”

Joris, who grew up in Luxembourg, the small duchy captured among the French and German -speaking worlds, identified with the linguistic confusion of the education of Celan in German and Romanian. Joris grew up talking about local Germanic dialect, Luxembourg, as well as German and French. (He called the French the “language of the bourgeoisie.”)

Luxembourg, he told Mr. Auster, “has the same complexities as the language in which Celan grew up”.

“That polyglot nature of Celan’s education, we share it,” he added.

Pierre Joseph Joris was born on July 14, 1946 in Strasbourg, France, from Roger Joris, a surgeon, and Nora Joris-Schintgen, who helped the practice of her husband as an administrator. He graduated from the Lycée Classique in Diekirch, in Luxembourg, in 1964, briefly studied medicine in Paris to satisfy his parents’ wishes, and then moved to the United States, where he earned a Bard from Bard in 1969.

In 1975, he achieved a master’s degree at the University of ASSEX in England in the theory and practice of literary translation. From 1976 to 1979, he taught in the English Department of the Constantine University 1 in Algeria. He achieved a doctorate of research. In the comparative literature of the State University of New York in Binghamton in 1990 and taught Suny Albany from 1992 to 2013.

In addition to his translations by Celan, Joris has published several volumes of his own poetry, including “Poasis: Selected Poems 1986-1999” (2001) and “Barzakh: Poems 2000-2012” (2014); Books of essays, including “A Nomad Poetics” (2003); And translations by Rilke, Edmond Jabès and other poets. He also edited anthologies, including “Poems for Millennium: the book of the University of California of modern and postmodern poetry”, with Jerome Rothenberg (1995 and 1998).

In addition to his wife, a performance artist survived a son, Miles Joris-Peyrafitte; A stepson, Joseph Mastantuono; And a sister, Michou Joris.

Asking to explain why it was attracted to the translation, Mr. Joris said to the periodic Arab literature in 2011: “Because, by chance of birth, I was blessed or damned by a lot of different languages and a perverse pleasure of putting them and their different music against each other”.