After making the space for 53 years, a rebellious Soviet spatial vehicle called Kosmos-482 returned to Earth, entering the planet's atmosphere at 9:24 in Moscow on Saturday, according to Roscosmos, the state company that manages the Russian space program.

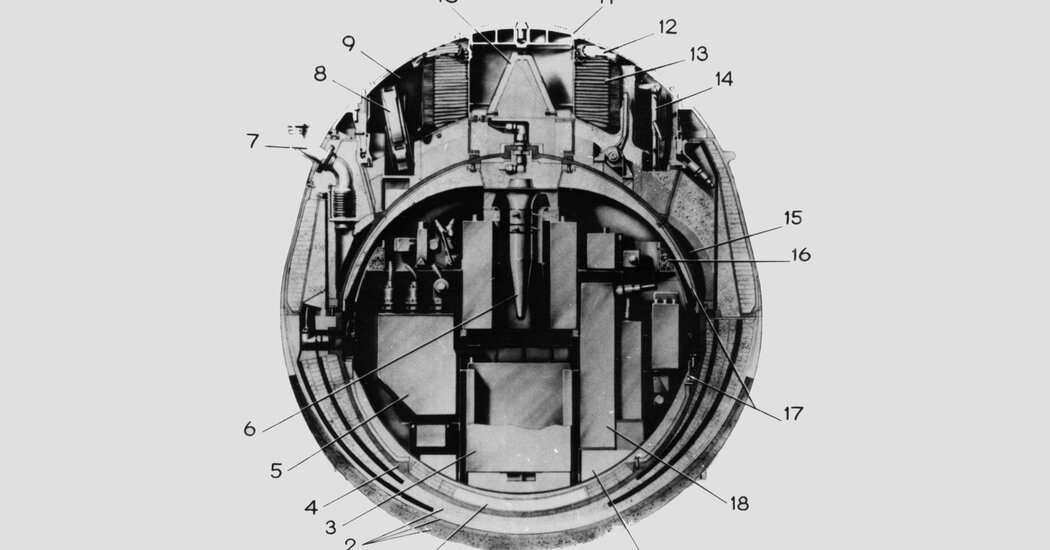

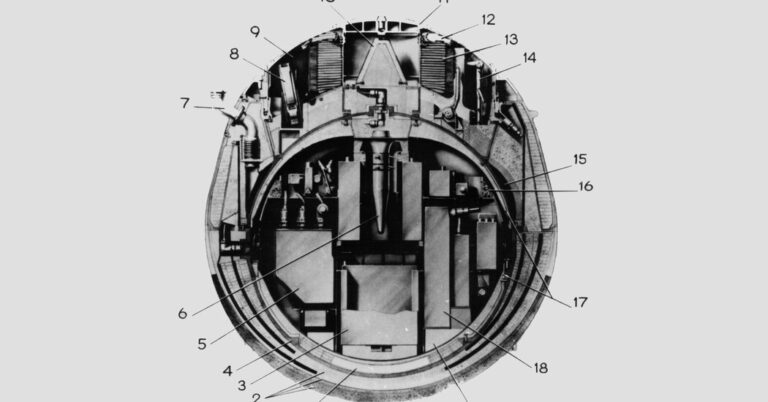

Designed to land on the Venus surface, Kosmos-482 may have remained intact during his dip. He splashed in the Indian Ocean west of Jakarta, Indonesia, said Roscosmos.

Kosmos-482 was launched on March 31, 1972, but stood in the terrestrial orbit after one of his rocket boosters closed prematurely. The return of the spacecraft to Earth was a reminder of the Cold War competition that pushed visions similar to science fiction of earth powers that projected into the sun system.

“Remember a time when the Soviet Union was adventurous in space – when we were all more adventurous in space,” said Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard & Smithsonian Astrophysics Center that keeps trace of the objects launched in orbit. “It's a little bit of sweet and sour moment in this sense.”

While America had won the race to the Moon, the Soviet Union, through its Venra program, kept its eyes on Venus, the Twisted sister of the Earth.

From 1961 to 1984, the Soviets launched 29 spatial vehicles towards the world wrapped next to it. Many of those missions failed, but more than a dozen no. The Venera spatial vehicle monitored Venus from the orbit, collected atmospheric observations while it was gently descended through its toxic clouds, collected and studied ground champions and sent the first, and only the images we have from the surface of the planet.

“Kosmos-482 recalls that, 50 years ago, the Soviet Union has reached the planet Venus. Here is a physical artifact of that project, of that time,” said Asif Siddiqi, historian of Fordham University, specialized in scientific spaces and activities of the Soviet era. “There is something strangely strange and compelling for me, on how the past still continues to orbit the earth.”

Half a century later, while the nations trace a return to the moon and launch their probes to Mars, Jupiter and various asteroids, a single Japanese space probe is the only vehicle in orbit in Venus. Other proposed missions have faced uncertain delays and future.

During the race to space, putting the boots on the moon was the largest prize, but also the other worlds of our solar system. While the United States concentrated more and more on Mars, the Soviet Union transformed the eyes towards the second rock from the sun.

“Both parties had an interest in Mars at that moment, but Venus was a simpler target,” said Cathleen Lewis, curator of international space and space programs at the National Air & Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution.

Almost the same dimensions of the earth, Venus is often defined as twin, although it is almost non-interne as the rocky planets get. It is covered in a dense atmosphere of carbon dioxide and hidden under miles of clouds of sulfuric acid. A victim of a greenhouse effect on the run, the Venusian surface is a 870 degree Fahrenheit and crushed by atmospheric pressure about 90 times greater than those of the earth.

“How do you build something that can survive a multimone journey through the sun system, get to a planet through a dense atmosphere, go to the ground and not melt or be crushed and take photos?” He asked Dr. Siddiqi. “It is a bit of an incredible problem to think of solving in the 1960s.”

Undaunted by the challenges posed by such a punitive world, the Soviets launched their hardware store in Venus, still and again. And at the moment there was no model on how to do it.

“You are literally inventing the thing you want to send to Venus,” said dr. Siddiqi. “Today if a country like Japan had to send something to Venus, they have 50 years of textbooks and engineering manuals. In the 1960s, you had nothing.”

The Soviet Venera program has reached a series of superlatives: the first probes to enter the atmosphere of another planet, the first space vehicle to secure safely on another planet, the first to record the sounds of an alien landscape.

Kosmos-482's failure occurred in the middle of that time sequence. And Saturday's return was not the first meeting of the Earth with the expected Venus Lander.

Around one in the morning on April 3, 1972, a few days after the troubled launch, the city of Ashburton, New Zealand, was visited by several 30 -pound titanium spheres, each of the size of a beach ball and marked with Cyrillic letters.

One ended up in a turnip field, which alarmed local citizenship. The New Zealand Herald reported in 2002 that one of the spheres “was finally blocked in an Ashburton police cell because nobody knew what to do with it”.

Although the spatial law specifies that the ownership of a crashing spatial object remains with the country that launched it, the Soviets have not claimed the ownership of the spheres at that moment. The “space balls” were finally returned to the farmers who found them.

And while Kosmos-482 was lost, his brother, who had been launched a few days earlier, in the end landed on Venus was called Venra 8. That spaceship survived and transmitted the data from the surface for 50 minutes. Two years later, when Venera 9 and 10 arrived – for the Soviets, building in redundancy meant launching two of everything – they fell slowly through the clouds, landed on the surface of the planet and transmit the images of a desolate and yellowish world.

The Venera program ended in the mid -1980s with the ambitious Vega probes. Those missions launched in 1984 abandoned the Landesi on the Venusian surface in 1985 and flew from Halley's comet in 1986.

“The legacy of the 70s and 80s of the Soviet exploration of Venus was a point of pride for the USSR,” said dr. Lewis.

The return of Kosmos-482, although unique for historical reasons, is not so unusual. Today, nations and companies are launching even more hardware in orbit, leaving no lack of objects that fall from the sky.

“The returns are very frequent now,” said Greg Henning, engineer and expert in space debris at the Aerospace Corporation, a non -profit organization supported at the federal level that keeps trace of the objects in orbit. “We are seeing dozens a day. Most of the time they go unnoticed.”

This is particularly true in the current moment, when the sun is quite active, because an increase in solar activity swells the terrestrial atmosphere and increases the resistance on orbiting objects.

Some of these returns organize spectacular light shows. They can derive from controlled paddles on Earth, such as those of the Spacex load and the crew capsules. Others are accidental, such as the failed test flights of the spacex astronavians prototypes. And others are deliberately uncontrolled and potentially quite dangerous, as happened with the missile boosters of 5 billion March in China, objects large enough to cause significant problems if they fall on a populated area.

But on rare occasions, an object like Kosmos-482 will return to Earth like a record of the first steps of humanity in the space that holds the earth.

“There is an archive of the space race, still around the earth. There are so many things that were launched in the 1950s, 60s, '70,” said dr. Siddiqi. “Sometimes we are reminded that there is this museum there because it falls on our heads.”

Jonathan Wolfe Contributed relationships.