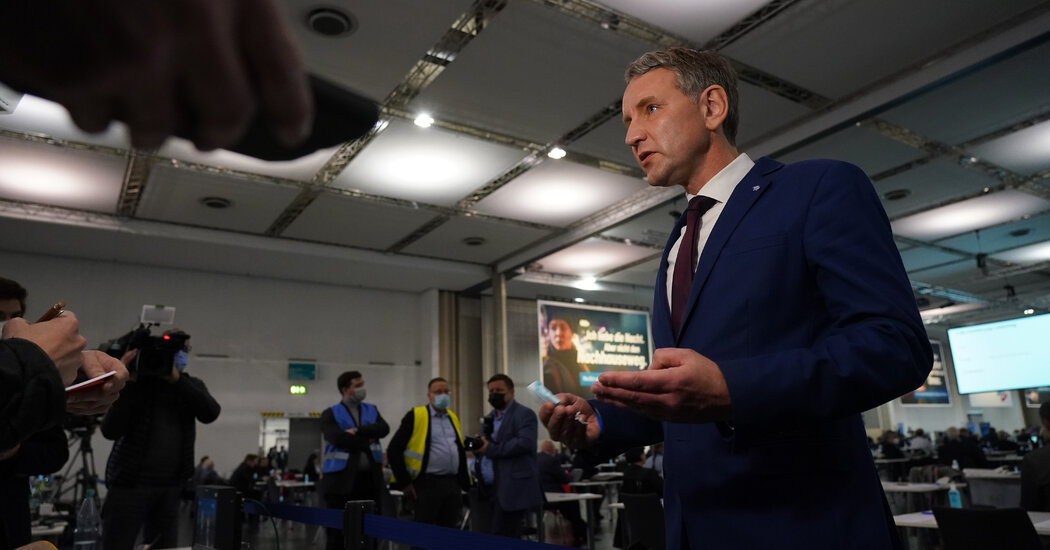

One of Germany's most prominent far-right leaders, Björn Höcke, went on trial Thursday on charges of using banned Nazi slogans at political rallies.

The use of National Socialist slogans and symbols is a punishable crime in Germany which, due to the legacy of Hitler's rise to power, has a much more restrictive approach to free speech than democracies such as the United States.

Mr Höcke heads the far-right Alternative for Germany party, known by its German abbreviation AfD, in the state of Thuringia. Both he and the state branch he leads have been classified by domestic intelligence as right-wing extremists and are under surveillance.

He is on trial for using the slogan “Everything for Germany” in a speech in the eastern region of Saxony, where he is on trial. It was the slogan of the National Socialist paramilitary group, or Storm Troopers, and it was engraved on their knives.

Mr Höcke said he did not know the phrase was a Nazi slogan. But critics have insisted the argument is not credible, given that he was a history teacher before becoming a politician. And they note that AfD politicians in two other states have already been stopped by authorities in past years for using the slogan.

The trial will take place in the city of Halle, at the state's highest court and is expected to last until May 14. Hundreds of people gathered outside the court at the start, chanting “All Halle hates the AfD” and “Together against fascism”. .”

If found guilty, Mr Höcke faces a short prison sentence or a fine. But the most worrying thing for him and his party is that the court could also temporarily revoke his right to vote and participate in elections. Such a decision would represent a major blow during a crucial election year in Germany, in which Höcke and the AfD are expected to get the largest share of votes.

In the three eastern German states that will hold elections later this year, the AfD is the most popular party. And domestically, it is performing better than all three ruling parties, despite mass protests that erupted nationwide after an investigative report revealed that some AfD members had attended a secret conference discussing of the deportation of immigrants.

The start of the trial on Thursday was delayed for several hours while Mr.'s lawyers Höcke applied for continuous recording of the hearings, which is not usually the case in German courts. They argued that without a full record, Mr Höcke, described as one of the most polarizing figures in Germany, would not receive a fair trial. The case would also have “historical relevance”, they argue, due to the growing influence of the AfD.

The AfD's latest resurgence began last spring, when it benefited from anxieties over rising immigration and frustration over the government's mismanagement of the country's stagnant economy. Chancellor Olaf Scholz's governing coalition appeared weak and divided everywhere.

Although the AfD is unlikely to take power in any of the three states, Höcke has become one of his party's most influential members.

Analysts say Höcke – a politician so right-wing that a court found it acceptable to call him a fascist – has not only succeeded in pushing his party further to the right, but also in pushing the broader political debate, particularly on issues such as immigration. Germany's largest party, the conservative Christian Democrats, for example, has taken an increasingly hostile stance on immigration.

Mainstream parties across the political spectrum have long vowed not to work with the AfD, and many are now seeking legal avenues to curb the party's influence in ways that have sparked debate over how much a democracy can act against the forces that undermine it.

AfD leaders like Höcke argue that they have become victims of state institutions that abuse their power to silence them. He recently posted comments on social media in English that caught the interest of Elon Musk, who asked because the slogan he used was illegal.

“Why is every patriot in Germany defamed as a Nazi, since Germany has legal texts in its penal code that are not found in any other democracy,” he he wrote in response. “These aim to prevent Germany from finding itself again.”

An accomplished orator, Höcke often sought to reintroduce words and slogans associated with the Third Reich, in what analysts describe as a two-pronged strategy.

“It's not random, it's well chosen,” said Johannes Hillje, a German political scientist who studies the AfD.

Such terms can serve as a sort of dog whistle for more extreme supporters of the right, he said. At the same time, Mr. Höcke chooses slogans that seem relatively banal.

Last week, during a television debate, Mr Höcke insisted that the slogan for which he had been prosecuted was so common that it had been used in an advertisement for Germany's main telephone operator, Deutsche Telekom. (The company denies this and has issued a cease-and-desist order against Mr. Höcke.)

Nonetheless, Hillje said, the effect is to make state institutions appear biased against the AfD because it is an anti-establishment force.

“It allows him to play the victim, and that works well for him and his supporters, because they feel like victims too,” she said.

Last week prosecutors successfully added a second charge against Mr Höcke to the trial. After being accused of using the slogan for the first time, he teased the chant at another political rally, shouting “Everything for…” to the crowd and letting supporters shout the final word: “Germany!”.