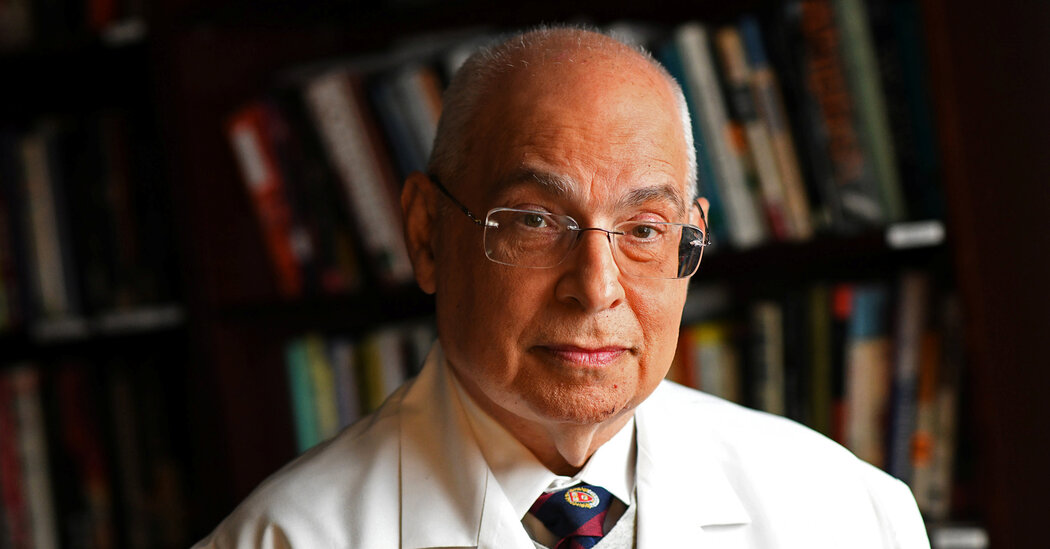

Dr. David Egilman, a physician and expert witness who, over a 35-year period, testified in nearly 600 corporate wrongdoing trials, winning billions of dollars in awards for victims and their survivors, died April 2 at his home in New York. Foxborough, Massachusetts. He was 71 years old.

The cause was cardiac arrest, his son Alex said.

Many medical experts have a sideline in court, offering their informed opinions on the witness stand and helping to validate or undermine plaintiffs' claims. But few make it a career-long passion like Dr. Egilman has. He taught at Brown University and ran a private practice, but spent most of his time consulting and testifying in as many as 15 cases a year.

He did more than just give opinions from the gallery. A tenacious researcher, he dug up incriminating emails and memos that showed that, in many cases, pharmaceutical companies knew the risks of bringing a new drug to market but went ahead anyway.

She provided critical testimony in a class action lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson, alleging that it failed to disclose health risks posed by Johnson's talcum powder and other talc-containing products. After years of litigation, the company settled for $8.9 billion in 2023.

Dr. Egilman's work as an expert witness rankled some people, particularly defense lawyers and pharmaceutical company executives, who argued that he was too dogmatic to provide an objective analysis. But Dr. Egilman saw things differently.

“As a doctor, I can treat one cancer patient at a time,” he said during a 2018 study. “But by being here, I have the potential to save millions.”

His work extended beyond the courtroom: He helped legal teams strategize their cases and coached them on how to present complicated medical data to juries.

“David was a game changer on so many levels,” said Mark Lanier, an attorney who worked with Dr. Egilman for 25 years. “David helped me in cases where he testified, but also in cases where he simply gave advice and insights.”

He also opposed what he saw as pharmaceutical marketing's intrusion into the realm of scientific research. Writing in peer-reviewed medical journals, he showed how drug companies used tactics such as ghostwriting – redacting their own studies and then paying a doctor to add their name – and “seeding,” in which companies conduct their own questionable studies to build support for their medications.

Dr. Egilman was instrumental in publicizing a declassified 1950 memo warning of the risks associated with government radiation testing on humans. The tests were carried out anyway.

“If this were to be done on human beings, I think that those involved in the Atomic Energy Commission would be subject to considerable criticism, for, admittedly, this would have a bit of a Buchenwald touch,” Dr. Joseph G . Hamilton, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, wrote in the note, referring to the Buchenwald concentration camp where Nazi doctors performed horrific medical experiments on prisoners.

The US government apologized for the radiation tests in 1996.

At times, Dr. Egilman's zeal got the better of him. In 2007, he agreed to pay drug company Eli Lilly $100,000 after leaking classified documents to a lawyer, who then gave them to the New York Times. He was involved in a lawsuit against the company over allegations that it had sold his antipsychotic drug Zyprexa for unapproved uses.

Eli Lilly donated the settlement money to charity. But the company's victory was short-lived: In 2009, it pleaded guilty to the charges and agreed to pay $1.4 billion, including a $515 million criminal fine, the largest ever in a healthcare case.

Dr. Egilman did not allow himself to be swayed by the ups and downs of the case.

“A doctor's oath,” he told Science magazine in 2019, “never says to keep your mouth shut.”

David Steven Egilman was born on September 9, 1952 in Boston. His father, Felix, was a Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust, including a stint in Buchenwald, because, he said, his shoemaking skills were prized by German officers. His wife and two children were killed in another concentration camp.

After the war, Felix Egilman emigrated to the United States, where he married Veta Albert, David's mother, who died in a car accident when David was 10 years old. His father withdrew emotionally in the face of mounting trauma, leaving David largely to care for him. of himself.

He won a scholarship to Brown University, where he earned a bachelor's degree in molecular biology in 1974 and a medical degree in 1978. He earned a master's degree in public health from Harvard in 1982.

Dr. Egilman married Helene Blomquist in 1988. Along with their son Alex, she survived him, as did another son, Samson.

After medical school and training at the National Institutes of Health, he moved to Cincinnati, where he opened a clinic within the United States Public Health Service. Many of his patients were industrial and mining workers who had developed medical conditions after years of working in unsafe environments.

The experience strengthened Dr. Egilman's resolve to stand up against medical injustice. He returned to Massachusetts in 1985, where he opened a private practice and began teaching at Brown.

To manage his growing list of legal clients, he founded a separate company, Never Again Consulting, a nod both to his father's experience during the Holocaust and to the importance of not allowing the horrors of Nazi medical experimentation to be replicated.