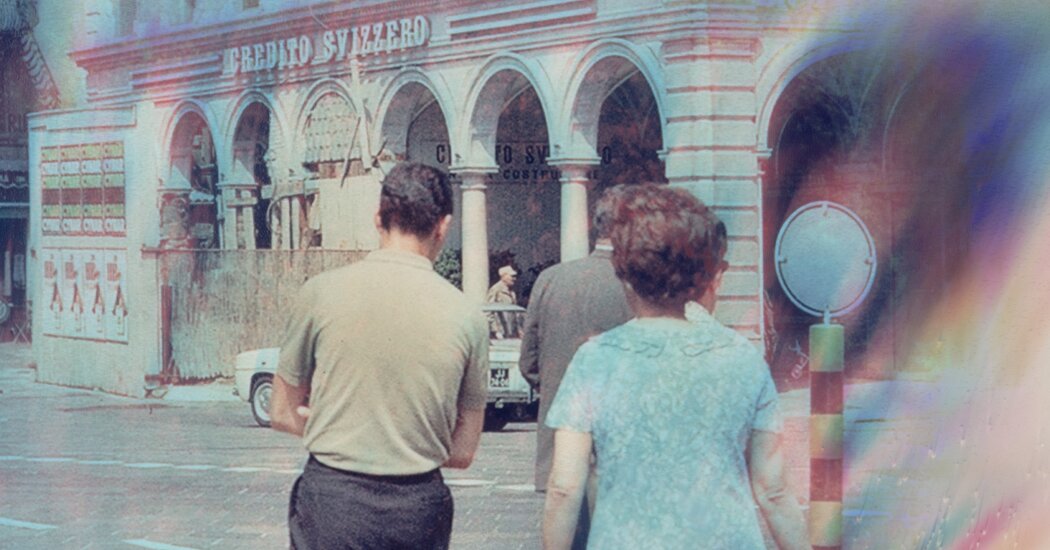

When I was a child, my father, who had left the country only a few times, told me about the trip he took to Europe with his parents when he was 14, in 1966. He told me how Nonie loved the immaculate Swiss streets and the flowerbeds that sparkled with flowers; the fireplace in the house on the hill outside Lugano, where his father was born, with ingenious alcoves on either side for hanging clothes or warming bread; the palpable poverty of the house in Pozzuoli, a town just outside Naples, where Nonie’s aunt had lined the walls with newspaper for better insulation. Every so often, my father would get out his projector and show me his Kodachrome slides.

As an adult, I spent years telling him that he and I should do the trip again—or at least a short version where we’d go to Switzerland and Italy, Lugano and Naples, so he could show me where his family came from. But now that his Alzheimer’s was worsening, that suggestion had taken on new meaning. Revisiting the past, I hoped, would help him live better in the present. A few years ago, I read about a palliative treatment for memory disorders called reminiscence therapy. The therapy involves activating participants’ strongest memories, those formed between the ages of 10 and 30, during the so-called memory bump, when personal and generational identity are being formed. Reminiscence therapy can take many forms: group therapy, one-on-one sessions with a caregiver, book collaboration sharing the patient’s story, or just conversation among friends. But the goal is the same: to comfort, engage, increase connection, and strengthen the bond between patient and caregiver.

One of the most immersive iterations of reminiscence therapy is a place called Town Square, an adult daycare for people with dementia. I visited shortly after it opened in 2018. The nursery consisted of an artificial village designed by the San Diego Opera to resemble a 1950s city. It had a diner, a beauty salon, a pet shop, a movie theater, a gas station and a town hall. By replicating the length of time during which participants’ brightest memories burned away, Town Square hoped to improve their quality of life. The decor offered much to talk about. In the living room, for example, hung a portrait of Elvis, and upon seeing it, a woman spoke of her adolescence, teleporting into her past. “There is no time machine except the human being,” writes Georgi Gospodinov in his novel “Time Shelter,” about a psychiatrist who develops memory clinics that simulate past eras. I was initially skeptical of the venture; warehousing people in a double-locked stage where oldies played 24 hours a day seemed grotesque. But what I witnessed there – spontaneous reminiscences in a cheerful environment – was perhaps the only positive view of Alzheimer's I saw.

I wanted this for my father, I wanted to give him a sense of joy now that he had closed the store, the place that was his world. Even if he wouldn't submit to adult day care, perhaps taking the journey back to 1966 would be like taking him back to a picture of his youth. In truth, I also wanted to replace the memories of the last terrible years with new ones, both for me and for him. I had spent the last 16 months making countless phone calls to his doctors, banks, and lawyers to negotiate insurmountable interest discounts. When he unknowingly undermined my efforts, making small, random payments or denying he had a disease, I would snap, and he would never hold it against me. No. He would vow to do better. Sometimes he would yell at me for being a nag and a “dickhead” (a demanding, controlling know-it-all, I think). But even when I pushed him to the point where he would hiss that I needed to move out of his house, I knew he loved me unconditionally and would apologize soon. He trusted me, even when I didn’t trust myself. Because of that, the ballast of my being, he asked for nothing in return, had no expectations. He never brought up a fight afterwards, and not just because of his disease. He didn’t hold a grudge like I did, vaguely, for the mistakes he had accumulated as his brain splintered, even though I knew none of it was his fault. And yet: why hadn’t he planned? Hadn’t he seen his mother suffer and fought to support her?