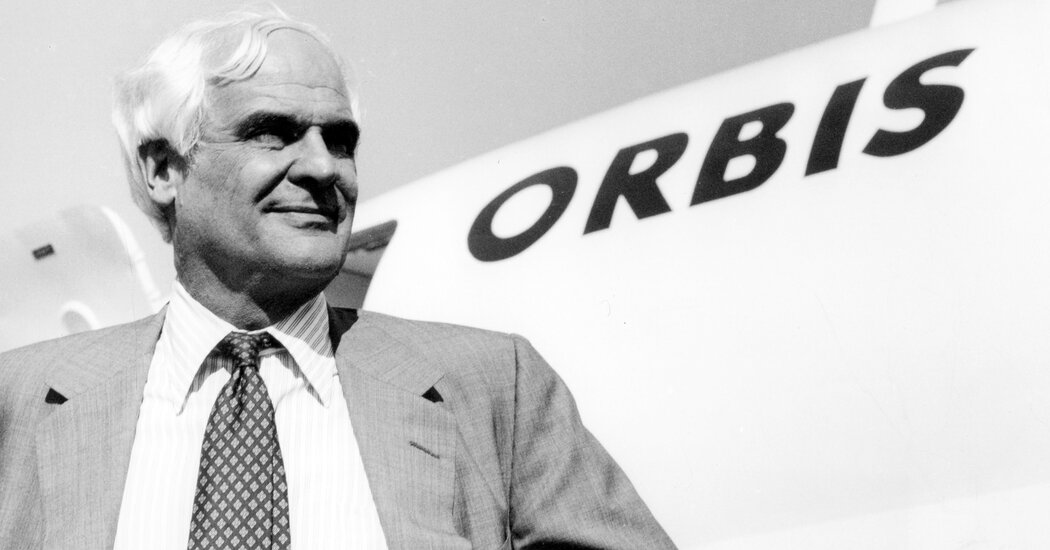

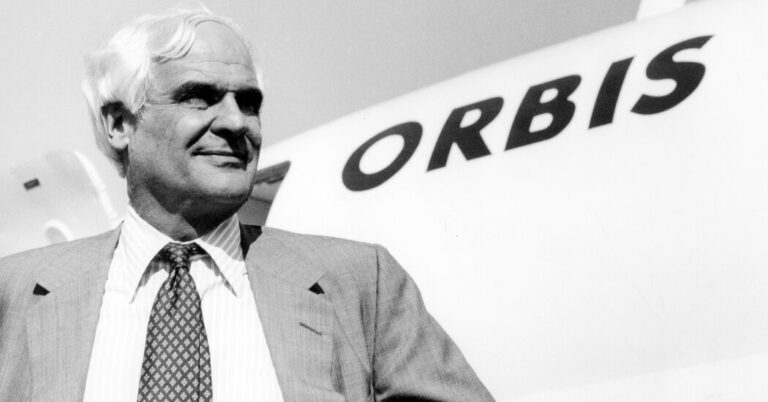

David Paton, an idealist and innovative ophthalmologist who started in Project Orbis, converting a United Airlines jet to a flying hospital that brought surgeons to developing countries to operate on patients and educate local doctors, died on April 3 at his house in Reno, Nev. It was 94.

His death was confirmed by his son, Townley.

Son of an important eye surgeon in New York whose patients included Iran's Shah and the lender J. Pierpont Morgan's Horse, dr. Paton (pronounced Pay-Ton tonne) was teaching the Johns Hopkins University Wilmer Eye Institute in the early 70s when discouraged by increasing cases increasing cases preventable in places.

“Other eye doctors were needed,” he wrote in his memories book, “Second Sight: views from A Eye Doctor's Odyssey” (2011), “but equally important was the need to strengthen the medical education of existing doctors”.

But how?

He considered the shipment of trunks of equipment – almost as a circus would do – but this had logistical challenges. He reflected on the possibility of using a medical ship like the one that Project Hope, a humanitarian group, has sent all over the world. It was too slow for him.

“Shortly after the first landing of the moon in 1969, thinking that Big was becoming a reality,” wrote dr. Paton.

And then an idea of the moon hit him: “A plane could be the answer? A fairly large plane could be converted into an operating theater, a teaching room and all the necessary structures”.

All he needed was a plane. He asked the military to donate one, but that was a non -start. He approached several universities to buy one, but the administrators refused him, saying that the idea was not feasible.

“David was willing to take risks that others would not have done,” said Bruce Spivey, founder of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, in an interview. “He was fascinating. He was stimulating. And he didn't stop.”

Dr. Paton has decided to raise funds alone. In 1973, he founded Project Orbis with a group of rich and well -connected figures such as the oil of Texas Leonard F. McCollum and Betsy Trppe Wainwright, daughter of the founder of Pan American World Airways Juan Trippe.

In 1980, Trippe contributed to convincing the CEO of United Airlines Edward Carlson to donate a DC-8 jet. The United States Agency for International Development has contributed with 1.25 million dollars to convert the plane to a hospital with an operating room, a recovery area and a classroom equipped with televisions, so that local medical operators could observe surgical interventions.

Surgure and nurses voluntarily offered their services, accepting to spend two or four weeks abroad. The first flight, in 1982, was in Panama. The plane then went to Peru, Jordan, Nepal and beyond. Mother Teresa once visited. So did the Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

In 1999, the London Sunday Times magazine sent a journalist to Cuba to write on the plane, now known as Flying Eye Hospital. One of the patients who arrived was a 14 -year -old girl named Julia.

“In the developed nations, Julia's conditions would have been little more than an irritation,” said the Sunday Times article. “It is almost certain that Uveite had an inflammation inside the eye, which can be canceled with drops. In Great Britain, cats are also easily treated.”

His doctor was Edward Holland, an important surgeon.

“Holland uses tiny knives to make openings that allow him to put his tools in his eyes, and soon he is pulling Julia's scar fabric,” said the Sunday Times article. “While the fabric is removed, a dark and liquid pupil is revealed, invisible for a decade. It is an intimate and moving moment; this is the chamber music of medicine. Subsequently, it breaks and removes the cataract and implants a lens so that the eye maintains its shape.”

The Cuban ophthalmologists who looked in the observation room applauded.

But after surgery, Julia still couldn't see.

“And then a minor miracle begins,” said the article. “While the swelling starts to go down, it makes discoveries on the world around it. Minute by minute can see something new.”

David Paton was born on August 16, 1930 in Baltimore and grew up in Manhattan. His father, Richard Townley Paton, specialized in corneal transplants and founded the eyeball for the restoration of the vision. His mother, Helen (meserve) Paton, was an interior designer.

In his memoir book, he described to grow “among the fine people, intellectually acute and widely traveled by the establishment”. His father was practiced on Park Avenue. Her mother organized parties in their home in the Upper East Side.

David attended the Hill School, a college in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. There he met James A. Baker III, a Texan who later became secretary of state for President George HW Bush. They were roommates of Princeton University and best friends for life.

“David came from a very privileged background, but he was on the ground and only a very nice boy,” Baker said in an interview. “He had his goals in life.

After graduating from Princeton in 1952, David graduated in Medicine from Johns Hopkins University. He worked in senior positions at the Wilmer Eye Institute and worked as president of the Ophthalmology Department at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

In 1979, while he was still trying to get a plane for Project Orbis, he became medical director of the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

“Among my duties”, he wrote in his book of memories, “he was providing eye care for many principles and princesses of the kingdom – about 5,000 of each, I was told – and it seemed that everyone insisted on being treated exclusively by the responsible doctor, it does not matter how less their complaint is less”.

The weddings of Dr. Paton to Jane Sterling Treman and Jane Franke ended with divorce. He married Diane Johnston in 1985. He died in 2022.

In addition to his son, he survived two grandchildren.

Dr. Paton left the role of medical director of the Orbis project in 1987, after a dispute with the Board of Directors. That year, President Ronald Reagan assigned him the medal of presidential citizens.

Although its official connection with the organization was finished, it was occasionally informal councilor.

Now called Orbis International, the organization is on its third plane, an MD-10 donated by Federal Express.

From 2014 to 2023, Orbis performed over 621,000 surgery and procedures, according to his latest annual report and offered over 424,000 training sessions to doctors, nurses and other suppliers.

“The plane is only such a unique place,” Dr. Hunter Cherwek, vice -president of the organization's clinical services and technologies, said in an interview. “It was just an incredibly bold and visionary idea.”